Voters in this pivotal state grapple with an unfamiliar emotion: hope.

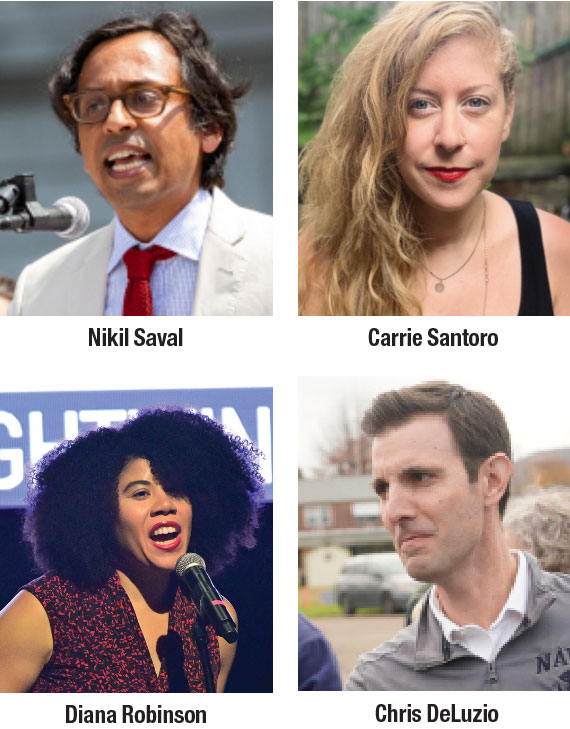

Marietta, Pennsylvania—“It takes a long time to build a relationship with someone to undo the 50 years of lies they’ve been told about themselves. That doesn’t happen in the two weeks before an election.” I’m sitting here on the banks of the Susquehanna River a few miles west of Lancaster on a sticky August morning, drinking iced coffee with Carrie Santoro, the executive director of Pennsylvania Stands Up. She’s explaining why her organization decided months ago that they were going to sit out the presidential campaign despite the fact that many election observers think Pennsylvania could decide the whole ballgame.

Like a lot of grassroots groups on the left, PA Stands Up went all in for Joe Biden and Kamala Harris in 2020. I’d spent Election Day with the group in Allentown and Reading, where its members, who had been told there might be trouble at polling places, worked around the clock knocking on doors, phone-banking, and making sure that Pennsylvania would—as their signs and hoodies proclaimed—“Count Every Vote.” In 2016, Donald Trump had won the state by fewer than 50,000 votes. In 2020, thanks in no small measure to the work of groups like theirs, Biden eked out a narrow victory.

Santoro grew up in a working-class family in Kutztown and became a mother when she was 19. Her son is trans, and she was initially drawn to activism over HB 2 (North Carolina’s infamous anti-trans bathroom bill) and “politicians using people like us to undermine gains for the working class.” Four years after Biden’s victory, she asks herself, “Has [his presidency] made any difference in the way people here talk about their lives, politics, prospects?” Her answer: “No.”

The impending Biden-Trump rematch has also failed to excite the members of PA Stands Up. And there was the fact that mounting a big get-out-the-vote effort in presidential election years left groups like hers “reliant on the influx of money that comes in…to carry us through municipal years when the money dries up.”

“You’ve doubled your staff and doubled your budget,” Santoro says. “But you haven’t doubled your power, because you’re moving into where philanthropy wants you to go.” In 2022, “that meant we were out there for [Senate candidate John] Fetterman and [gubernatorial candidate Josh] Shapiro. Those were heavy lifts” for her group.

In 2023, PA Stands Up pivoted. “We focused on rural and small-town PA, recruited dozens of volunteers, and endorsed 58 people for municipal office in northeastern PA—Lehigh, Lancaster, and Berks counties. Everything from school board slates to county commissioners. We did 127,000 door knocks. Thirty-five of our candidates won…. Staring down the barrel of Biden-Trump II, we were not going to get sucked into that again. No, thank you!”

Instead, PA Stands Up decided on a “reverse coattails” strategy: not mentioning Biden or Harris on the doorstep or in their literature, but focusing on local races and local issues to organize voters—who might then also support the top of the ticket. A few days before our meeting, Harris introduced Tim Walz as her vice presidential pick to cheering crowds in Philadelphia. “Last week was very exciting,” Santoro tells me. “All of us were fucking shocked it wasn’t Shapiro!” Responses to the new ticket “ranged from relief…to elation.” Her group still hasn’t changed its game plan. But that sense of fresh energy and renewed possibility greeted me almost everywhere I traveled in Pennsylvania, from the banks of the Delaware to the shores of the Ohio.

The sole exception was Altoona, a former Pennsylvania Railroad company town in central Pennsylvania that today is home to the corporate headquarters of Sheetz, the convenience store chain frequently invoked by Fetterman as a badge of his adoptive Yinzer (Pittsburgh-area) identity. (He was raised in the state’s eastern portion.) I spent a long half-hour at Peoples Natural Gas Field, the ballpark of the Altoona Curve—the Pittsburgh Pirates’ Double-A affiliate—trying to find a Democratic voter to interview before the retired American Sign Language teacher sitting next to me put me out of my misery. “This is Trump country,” he told me. “You won’t find any Harris supporters here.”

One reason for that, I was told, was the Democrats’ purported hostility to fracking. The railroads that built Altoona and brought jobs, prosperity, and immigrants into most of central Pennsylvania ran on coal—both the hard anthracite known as “black diamond,” found in the northeastern part of the state (used in iron and steel production), and the soft bituminous coal (used for power and heat) that lies under most of the Alleghenies. Although 2022’s total of just under 40 million tons is a far cry from the 276 million tons taken from the state’s coalfields in 1918, Pennsylvania’s long history of mining and smelting has produced a working class that associates dirty jobs—and foul air—with steady work.

But race might also have been a factor in the city’s support for Trump. According to a 2022 Washington Post article, Altoona’s 122,000 residents are 94 percent white, making it the second-whitest city in the country. And while the atmosphere at the ballpark was friendly enough—even during my futile search for Democratic voters—the only Black or brown people I saw that evening were wearing uniforms on the field.

It was James Carville who coined the conventional wisdom about this state’s contradictory politics. Philadelphia and Pittsburgh are both big Democratic cities, but “between Paoli [at the western end of Philly’s Main Line suburbs] and Penn Hills [just east of Pittsburgh], Pennsylvania is Alabama without the Blacks,” he quipped. “They didn’t film The Deer Hunter there for nothing.”

That was back in 1986, when Carville was working as a consultant to Democratic Governor Bob Casey Sr.—whose US senator son is up for reelection to a fourth term in November. Thirty years later, in 2016, a failed candidate for the state’s other Senate seat drove me to Clairton—the town near Pittsburgh that furnished the main setting for The Deer Hunter—so I could see the devastation for myself.

“Hillary Clinton thinks America is already great,” John Fetterman said to me then, explaining why neither Kat McGinty, the energy company executive who’d beaten him for the nomination, nor Clinton herself were likely to win his state that November. As we headed down the Mon Valley from McKeesport to Clairton, Fetterman lowered the windows of his pickup truck so I could smell the coke works, which he said gave the town the worst air quality in the country.

“American steel production was gutted by NAFTA,” he told me. “And if the coke works goes, I don’t know what the folks here will have left.”

Eight years, one catastrophic stroke, and a thousand memes later, Fetterman now sits in the Senate. As for the Clairton Coke Works, it is still the most toxic polluter in Allegheny County, and it still stinks. The works’ owner, US Steel, has recently been fined $11 million by the county health department, but neither Trump’s “Drill, baby, drill!” approach to fossil fuels nor Biden’s professed fondness for a green energy revolution have made much difference to the air quality here.

As in 2016 and 2020, this year’s election might all come down to Pennsylvania. There are paths to victory for both Harris and Trump that don’t rely on this state’s 19 Electoral College votes—the biggest prize among the swing states, with more electoral votes than Wisconsin and Nevada or Arizona and Nevada—but those paths are far more perilous. Which is why I returned to the state where I’d attended elementary and middle school (in northeast Philadelphia) and worked summers, like Kamala Harris and Doug Emhoff, flipping burgers at McDonald’s (in my case in Reading, where my parents moved while I was in college). I might not have kept up with the all the news, but the local accent—easily detected in the way they pronounce “attitude” as “atty-tood”—was on a frequency I could still tune in to.

While outsiders sometimes deride the state’s less enlightened regions as “Pennsyltucky,” locals refer to the portion of the map left when you cut out Pittsburgh and Philadelphia (and its suburban “collar counties”) simply as “the T.” I first got a sense of the changes in the T when I visited Reading. Like Milwaukee, Reading had been an outpost of so-called sewer socialism in the early 20th century, famous for the efficiency and probity of the city’s socialist administration. Then deindustrialization hit hard. By 2020, Pennsylvania’s fourth-largest city—notorious during its long decline as the hometown of Roy Frankhouser, a Grand Dragon of the Ku Klux Klan and a fervent American Nazi—had become nearly 70 percent Latino. The mayor, Eddie Moran, who told me he was born in Puerto Rico and raised in Brooklyn, represented a new wave of immigrants. Forced out of New York by gentrification, many were drawn here by the plentiful supply of inexpensive housing, vibrant communities from Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, Mexico, and Colombia, and steady (if low-wage) jobs in nearby warehouses and food processors. Called the poorest city in the country by The New York Times in 2011, Reading remains poor. But a population that had been sharply declining since 1930 has grown in each of the last three censuses.

Asimilar process has been at work in Hazleton, about 55 miles north of Reading. The drive wound past Frackville, through Carbon County and past the Atlantic Coal Company’s Hazleton Shaft site, to a tattered community center where I spoke with Diana Robinson, the co–deputy director of Make the Road Action PA, a group that since 2014 has been organizing among immigrant, poor, and working-class communities across the state. MTR and PA Stands Up were far and away the most effective of the grassroots groups I saw doing electoral work here in 2020—not just sending out hundreds of canvassers but coordinating well-organized trainings and teams devoted to ballot access and election security. So I wanted to ask them what they’d learned from that experience, and what four years of a Democratic administration had meant for their members.

“‘Pennsyltucky’ is not true anymore,” Robinson began. “In this part of the state, the fastest-growing populations are Latinos and AAPI [Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders]. After Hurricane Maria [which devastated Puerto Rico in 2017], we saw a lot of immigration to Allentown, Lancaster, the Lehigh Valley. There’s been significant growth of the BIPOC population in almost all of the state’s 67 counties.”

The daughter of immigrants from Colombia and the Dominican Republic, Robinson is a product of East New York and CUNY, where she got a master’s degree in labor studies before joining the Food Chain Workers Alliance. “After the election of Trump, I saw a lot of value in how we are organizing our communities around the vote as a tactic to build power.” At the same time, she saw “so much passivity, cynicism. People said, ‘You’re not really gonna change anything.’ But then AOC got elected. Jessica Ramos got elected.”

Those victories taught Robinson that “we can win.” Which in turn led her to wonder: “So how do we think about governing?” In one form or another, this was a question that recurred throughout my travels.

“The Pennsylvania minimum wage hasn’t gone up in almost 25 years,” Robinson told me. “It’s still $7.25—in 2024! The House of Representatives in Harrisburg has passed an increase several times. But the state Senate hasn’t moved.” For her members, many of whom rely on minimum-wage jobs, this isn’t just a moral issue. Neither is immigration—especially medical deportations, in which private contractors profit from removing indigent patients from local hospitals. The practice was banned by the Philadelphia City Council in December thanks to pressure from MTR and other groups, but it remains legal elsewhere in the state.

“We know candidates are not going to check off all our boxes,” Robinson said. “But it makes a difference having people we can move in office, and who we can hold accountable.”

After Biden’s inauguration, MTR decided to “focus heavily on the local—primaries, state Legislature races, and grand auditor and attorney general [statewide downballot offices]. Our goal was to keep the majority—currently one member—in the state House and increase it, and to try to flip the state Senate,” Robinson said. She pointed out that one of the candidates endorsed by MTR, Anna Thomas, lost her state House race by fewer than 700 votes to an incumbent with a 0 rating from Planned Parenthood, and that another, Johanny Cepeda-Freytiz, is now the first Democrat to represent her district in Harrisburg since the 1960s.

The group’s goal for 2024 is relatively modest—if urgent. “Right now the focus is on blocking,” Robinson said, echoing language I’d first heard used by Maurice Mitchell, the national director of the Working Families Party, “and then later on we can build.”

But since Biden withdrew in favor of Kamala Harris, Robinson has noticed “there is a little more enthusiasm. More of an opportunity to push, to move. Younger folks—we’re still not convinced. But older women and older Black men were excited. There’s a little more hope.”

“We have the ability to speak to people who are disaffected with both parties, because we’re outside the system. We’re not Democrats,” Nick Gavio told me. The mid-Atlantic communications director of the Working Families Party, Gavio grew up in Hazleton. He worked for Fetterman before joining the WFP.

Gavio reminded me that a former mayor of Hazleton, Lou Barletta, responded to the growth in the local Latino population by passing a law allowing the city to revoke for five years the business permit of any employer who hired an undocumented immigrant, as well as to fine landlords up to $1,000 per day for renting to anyone undocumented. Barletta parlayed his bigotry into a seat in Congress in 2011—where he proposed a bill penalizing sanctuary cities and cosponsored a bill to bar DACA recipients from enlisting in the military—then lost his challenge to Bob Casey Jr. for the Senate. But Gavio also reminded me that a growing Latino population does not always translate into more Democratic voters. Bethlehem, where the shell of what was once the second-largest steel mill in the country now houses a hotel and casino complex, has become both more Latino and more Republican.

But then party politics in this state has never been simply by the numbers. “According to party registration, in the coal-mining counties, bears still outnumber Republicans,” Gavio said. “Even though Republicans have won those counties for decades.”

The WFP’s activities in Pennsylvania are centered on Philadelphia, where, thanks to a quirky law that prevents any political party from nominating more than five candidates for the seven at-large seats on the City Council, the WFP now boasts two council members. Plus, Gavio said, the party has “a pretty deep bench of state legislators” as well as Summer Lee in Congress. Describing the WFP’s constituency as “young voters, progressive voters, disaffected Black voters—the multiracial working class,” he said the party also had strength in Pittsburgh, Allentown, and the Lehigh Valley.

Gavio, too, noted a change in the political weather from “what Maurice calls ‘block and build’” to something more ambitious. Noting that the group had just endorsed the Harris-Walz ticket, he said, “An endorsement isn’t a love letter. There are still ways we need to push Harris. But we can disagree on issues and still support her. In left circles, we’re seeing energy that was not around previously. People are more excited.”

I caught up with Representative Chris Deluzio at a seniors’ lunch in Sharpsburg, an overwhelmingly white section of Pittsburgh on the north bank of the Allegheny River. The housing stock, Deluzio said, is “really old.” His district includes all of Beaver County and a slice of Allegheny County: “Mill towns, new city neighborhoods, suburbs, farms.” In 2022, the freshman congressman won by seven points—besting Biden’s performance in 2020 and improving on that of Deluzio’s predecessor, Conor Lamb, who mounted his own failed bid for the Senate.

Deluzio is an improvement on Lamb—a poster boy for centrist corporate Democratic donors—in other ways as well. “When corporate power and wealth have their way, our communities are gonna be collateral damage,” he told the seniors, at least one of whom was wearing a MAGA hat. Afterward, he elaborated: “Free trade was bullshit. It hurt our communities. The whole thing was a plan to strip us for parts. But that ship is turning around. Now we’re beginning to see union power, with worker power backing it up. Speaks to where the party has to go.”

An Annapolis graduate with a law degree from Georgetown who served in Iraq, practiced in New York, and worked at the Brennan Center policy institute before running for office, Deluzio is a cosponsor of Medicare for All. But his signature issue is probably rail safety. “When East Palestine happened,” he said, referring to the Norfolk Southern train derailment in Ohio, “parts of Pennsylvania were in the evacuation zone. Those were my constituents.” Norfolk Southern’s huge Conway Yard is in his district. “About 48 percent of my constituents live within a mile of the tracks—90 percent within five miles.”

In the wake of the disaster, Deluzio and Representative Ro Khanna of California introduced a bill in the US House to tighten the regulations governing the transportation of flammable and hazardous materials. Ohio’s Sherrod Brown and JD Vance introduced parallel legislation in the Senate. More than a year later, neither has come to a vote. “Who lobbies against rail safety?” Deluzio asked. “The Koch brothers—who are bankrolling my opponent!”

Yet he, too, derives hope from the change at the top of the Democratic ticket. Deluzio was already a Biden fan. “This has been the most pro-union administration in my lifetime,” he said. But now “there is real enthusiasm. Small-dollar donations are up. And you can see it in who shows up for events.”

I got a similar response from Nikil Saval, the n+1 magazine editor and writer turned politician, who, thanks in part to the WFP, now represents downtown Philadelphia (SD-1) in the state Senate. “Every time Biden’s name came up [on the doorstep], it was a disaster,” he told me. “We had all these workarounds… the lengths people had to go to. I couldn’t really see a path to victory—and that was even before the debate.

“Before Harris, the Democrats’ one-vote margin in the state Assembly was in jeopardy. In the Senate, we’re only in the minority by three seats. Now there’s hope of flipping the state Senate seat against [Allegheny County’s Devlin Robinson,] the Republican chair of the Labor Committee.”

Saval also pointed out that “since 2020, some progressive infrastructure has taken shape” in Pennsylvania—much of it fueled by former Bernie Sanders campaign activists like him. He noted that in addition to the WFP, MTR, PA Stands Up, PA United (active around Pittsburgh), and Reclaim Philadelphia (Saval’s group, which started with 35 Sanders veterans and now has 660 dues-paying members and fields hundreds of volunteers), the “SEIU Healthcare [union] is very important around Pittsburgh,” and the American Federation of Teachers is also a power in the state.

Ieven managed to detect a flicker of optimism from Pittsburgh native Damon Young, the acerbic writer, critic, and author of What Doesn’t Kill You Makes You Blacker—though he quickly qualified it: “Much of the excitement is a repurposing of relief. A month ago, things seemed pretty dire.”

I first met Young back in 2016, when he underlined the threat Trump’s first campaign posed to Black Americans. “I look at him as a proxy,” Young told me then. “He’s dangerous because he’s popular.”

The intervening eight years haven’t softened Young’s outlook. “Have things changed? Yes. But for the worse. It’s become more difficult for me as a Black person. More difficult to do what we [writers] do for a living.

“Things were never great.” But, Young added, after the initial outpouring of the 2020 racial justice protests in the wake of George Floyd’s murder, “I’ve encountered more cynicism, more pushback, more fear.”

So while he is not surprised when friends tell him they’re not voting, “I’ve never been that far left. And I have no trouble seeing a distinct difference between a President Trump and a President Biden. But then I’ve never been a policy wonk. For me, it’s more about sensibility.”

And on the level of sensibility, Young, too, has noticed a change. “Trump seems to be flailing.” Then he caught himself. “Of course, things could change between now and November.”

The last stop on my Pennsylvania road trip was Aliquippa, a dying steel town north of Pittsburgh on the Ohio River. There, I met with the Lee sisters—Tamika, Latesha, and Heaven—who make up the entire paid staff of Beaver County United. We were joined by Kyla Rollins from PA United. As it happens, Harris, Walz, and their spouses would arrive in town a few days later. Both candidates addressed the high school football team—the Quips, an apparently all-Black squad that won the state championship in December and then had to sue the PIAA, the governing body for high school sports in the state, to keep from being bumped up into a division in which they would have to compete against much larger and wealthier schools.

The Quips prevailed in court as they had on the gridiron, and the event—where Harris and Walz told them that, like football, politics “is about setting a future goal and trying to reach it”—made for great visuals, an upbeat TikTok, and even a post in The New Republic. But in less than a day, the local news would move on to the murder of Treonna Washington, a 20-year-old woman whose body was found in an alley.

When I asked the Lee sisters how this election looked from Aliquippa, Heaven responded, “In 2020, there was so much hype around getting Trump out of office. What did Biden actually do, when nothing in our community is changing? Right now, our focus is on youth violence, gun violence, police brutality, and housing.” They also complained about a new petrochemical plant in nearby Monaca, which was supposed to bring jobs and prosperity—but has instead brought only pollution, sickness, and bitter disappointment.

“The people in the community don’t see much change here,” Tamika said. “They don’t feel much motivation to vote. It feels like nobody hears us.”

Yet even in Aliquippa—where broken promises are the only promises on offer from politicians—Tamika, who had begun by saying, “A Harris-Walz ticket is not a golden ticket to a brand-new Beaver County,” ended on: “Now, with Harris, it feels like, ‘Hey, we have a fighting chance.’”

That was before the candidates’ visit. But this disconnect between experience and expectation—or between cynicism and cautious optimism—was the one constant on my travels. After I left Pennsylvania, I saw the photos of Harris and Walz with the Quips and with the seemingly all-white Aliquippa Fire Department. However, I couldn’t find any evidence that the campaign had much contact with the non-uniformed residents of this increasingly diverse, persistently despairing city.

In trying to make sense of all this—not only the conflicting narratives, but the huge disparities just beneath the surface, even in an apparently thriving city like Pittsburgh, whose patented mix of “meds and eds” (big hospitals and prosperous universities) keeps it high in the rankings for “most livable city”—I kept coming back to something Damon Young said.

When I asked him why the white progressives and Black activists in his part of the state seem to have so few points of contact, he replied, “Any conversation about racial dynamics has to start from the fact that Pittsburgh is the whitest big city in the country.” (Eighty-five percent white, according to the Census Bureau.) “It’s also the worst city in the country for Black women.” Later he sent me an article detailing how “poverty rates, birth defect rates, death rates, unemployment rates, and school arrest rates” were higher there for Black girls and women than elsewhere in the United States.

Back in 1936, the novelist John Dos Passos described the shock of discovering that, for all the appearance of a common culture, America remained “two nations” in a book titled The Big Money. For Dos Passos, it was class, not race, that marked the fundamental divide. Spend any time in Pennsylvania, though, and you begin to sense both the entrenched persistence of that chasm and the ways that race and class intertwine to weave it into the structures of our lives.

For a brief eight years, during the Obama presidency, it became fashionable to talk about a post-racial America. Yet as Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor noted, “with great expectations came even greater disappointments.” Followed by four years of Donald Trump.

As a speaker, Kamala Harris is no Barack Obama—that much, at least, was clear from the convention in Chicago. But she, too, has summoned great hope. And unlike the man she replaced at the top of the ticket, she actually has a chance of winning on November 5.

Ihad last seen Jane Palmer on Election Day 2020 in Reading, wielding a bullhorn and encouraging drivers to honk if they’d voted for Biden and Harris. A cofounder of Berks Stands Up, Palmer is a veteran activist who, at some point over the past four years, realized that she had burned out.

When we met over Chinese dumplings in Philadelphia this August, she was still leery of presidential campaigning. “You build power slowly and strategically and methodically,” she said. “A presidential campaign does not do that. It gets people all stirred up—and then they’re gone.”

Yet she, too, admitted to flickers of optimism, partly due to the change at the top of the ticket. Mostly, though, because of the way Harris and Walz talked about their lives. “The work that we did changed the narrative. It made it normal to talk about basic needs: healthcare, safe places to live and raise our kids. Which made it possible for Tim Walz to stand there and talk about what he’s talking about.”

Palmer is still focusing on local issues this cycle, especially prison reform. But she has been unable to remain on the sidelines. “I’m currently begging the Democratic Party to let me canvass my own neighborhood.”

“We’ve trained people to feel stupid, ignorant of politics,” she said. “But it isn’t really that complicated. All you have to know is what you want.”

D.D. Guttenplan

D.D. Guttenplan is editor of The Nation.